Vanessa Gordon

LEARNING FROM THE SLOW PROFESSOR

LEARNING FROM THE SLOW PROFESSOR

II.The Problem

III.Deep Thinking

Accomodating Student Schedules

For both good and bad reasons, educators are ever more efficient, and so are students. This said, this efficiency does not always lend itself well to good teaching or learning.

I. INTRODUCTION

I was an exhausted teacher. In the classroom, I spoke as quickly as I could and exhorted my students to write faster. I often didn’t have enough time to finish what I wanted to cover. Unsurprisingly, I wondered how much my students were learning.

I questioned whether some of the active learning materials were efficient at addressing the course objectives, I was much more comfortable coaching my students through writing a paper than I was getting them to participate in an organized simulation. This is still the case.

Outside the classroom, I had the impression that I was caught in a hamster wheel of continuous grading and feedback. Other than that, I spent copious amounts of time managing emails, managing student problems, troubleshooting facilities and attending meetings. It felt as if there was no more room to prepare the class activities and keep up to date on the course content.

Observing my dilemma, when my partner saw the book The Slow Professor (Barbara K. Seeber and Maggie Berg, University of Toronto Press, 2016) he knew that it would be special to me. In many areas of my life, I’m a fervent adherent of the Slow Movement. Slow living isn’t a simple matter of just ‘slowing down’: it is an issue of cultivating agency through observation, deliberation and reflection. It seeks to live in the present in a meaningful, sustainable, thoughtful and pleasurable way.

I grow my own vegetables. I ferment, can and dehydrate. I have a root cellar. Slowly but surely, I have been eliminating processed food from our diet and plastic from my kitchen. Pleasure is important. Our house often hosts happy dinner guests and I’m told on a regular basis that the food is exceptional.

The slow movement also applies to raising children. I’m a regular reader of writings on the subject. Although I’m far from perfect at it, I feel that my children have benefited greatly from the approach.

So why not Slow Teaching?

The Slow Professor’s first observation is that my experience is far from unique: teachers right across the Canada and the United States are feeling the exact same pressures. The book points out the irony of being hired to think and not having enough time to do just that.

This report will focus on the insights that The Slow Professor by Barbara K. Seeber and Maggie Berg has lent to my approach to student writing.

II. THE PROBLEM

The hamster dilemma is one largely a result of a work mandate that isn’t regular or even predictable: at any given week, we cannot anticipate the number of plagiarism cases that need addressing, student accommodations for illness or disability that need to be organized, reference letters that students might ask for, students in distress that need counselling, interesting projects that crop up, meetings, talks, trainings, broken projectors etc. etc.

Added to this are the tasks that are regular in occurrence but variable in time intensity. Student papers can always use more feedback, there is always more scholarly material to read to keep up to date, there are pedagogical materials to read and take into consideration, class activities to update, new technologies, increasing class sizes, and increasing clerical tasks.

What do teachers do? They respond by being more productive. They set time limits to each of their tasks and try to get as many done as possible in any given week. They try to do things quickly to increase their efficiency and they try to market their achievements at least a little bit.

On the face of it, this is fine. However, the results are highly fragmented days. Not to put too fine a point on it, the more we get on that hamster wheel, the more we train ourselves to respond to *everything* and just get it all done, the more we end up with hamster brains. It just isn’t conducive to deep thinking.

III. DEEP THINKING

Deep thinking is the magic ingredient that’s missing when we spend all our time scrambling to ‘get things done’. What’s needed is the understanding that good teaching doesn’t happen without time for reflection.

The time referred to here is sometimes called ‘flow’ in psychology, or ‘timeless time’ in communication theory. It’s when one loses track of time absorbed in what they are doing. According to Charalampos Mainemelis, achieving this is often done when one is engaged in a creative endeavor to achieve worthwhile goals.

When I lose track of time while working, my first reaction often is to feel frustration at ‘letting time get away from me’, and a sense of panic about all the little things I should have gotten done. What I need to understand is that not only is it OK to lose track of time, this produces great work. I should lose track of time and be happy, and if I can replicate this in the classroom, I’ve done my job.

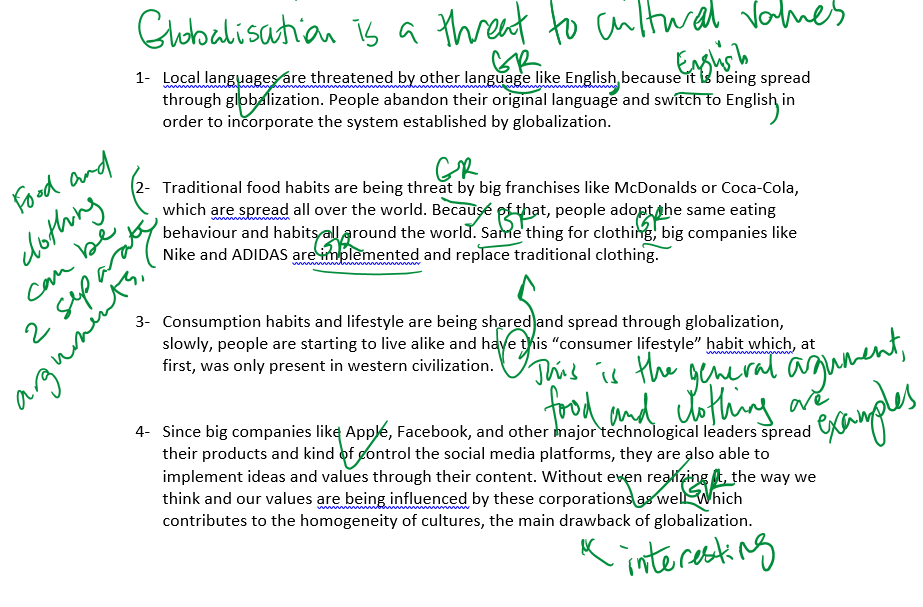

Bean et al.’s work on supporting deep thinking through student writing has been extremely useful. I use Dean Drenk’s thesis support short essays in all of my classes. Thesis support lends to deep thinking because for students, coming up with a thought-provoking thesis is extremely hard, and so when left to their own devices, they often write a broad statement that often leads to what John Bean describes as ‘data dumps’. Learning to write a thesis is battle best left for Integrative Seminar. When students are free to choose a side of a controversial topic through a well-constructed thesis, they can engage in focused argumentation. In addition, by giving the students the opportunity to choose a side on a controversial topic, they will be able to see Politics as a discipline that requires a good understanding of complex concepts and theories, and not about memorizing a body of facts, which is not deep thinking.

In his book Engaging Ideas, John C. Bean also discusses the importance of getting students to think about ‘audience’ and ‘purpose’ in their writing. I think that for students, the ability to understand the audience and purpose of their thesis support short essays is key to engaging deeper thinking. I’ve been developing an exercise where students read selected bits of award-winning research in political science, and they discuss the who the author’s audience might be, as well as the purpose of their work. They are later tasked to come up with a ‘vision statement’ for their own short essay, which makes explicit the purpose and importance of their research. My theory is that if I can explain this properly, student writing will again reflect deep learning. This component of my classes is still in development.

Broadly speaking, during my time at WID I identified two strategies to help alleviate time pressures and create time to think. The first concerns ‘optimization’, and the second is about identifying bad uses of time in our daily functioning.

IV. OPTIMIZATION OUTSIDE OF THE CLASSROOM

Admittedly, ‘optimizing for time’ isn’t particularly in the spirit of Slow Learning. Be that as it may, there is wisdom in the knowledge that while we want to slow down, some things can still be sped up in order to take it slow where it counts.

FEEDBACK

Feedback is vital to student learning and by extension, good writing. My thesis support assignments are scaffolded. Students choose the thesis and write the essay outline and their vision statement before attempting two body paragraphs, then the introduction and conclusion. The thesis support assignments are also extremely iterative: students are encouraged to revise, revise and revise again, resubmitting as many times as they need before putting the ensemble together. When it works properly, the teacher establishes a regular line of communication with each student parallel to the communication that takes place in the classroom. Like it or not, consistent, regular coaching for each student is worth the time investment. This process takes an enormous amount of teaching time.

Instead of taking in paper copies, I optimized by asking my students to submit the digital file of their work on LEA. After that, I used to type my comments directly into their file. This took forever.

After a few semesters of this, I switched to using voice-to-text software to provide the students a monologue of my thoughts as I read their work. It worked to a degree, but it was a bad way to give students information in a form that they could readily use to update their work.

Last summer I took the decision to invest in a computer with a touch screen and a smart pen. This allows me to mark up a document much as one would mark up a hard copy, save the changes and resubmit them to the student. In this way, both the student and I have a copy of the feedback, and the student can simply delete each comment and update their file as they go. Some teachers may object to the cost of this solution: this is an expensive proposition and the cost comes out of the teacher’s wages. This said, it is the solution that works best for me now.

Feedback elements that I have incorporated from John C. Bean’s work include the use of rubrics, and peer reviews of drafts. Other aspects of my grading that I’m working on is ‘coaching revision’ and revision-oriented commenting strategy to improve student grammar.

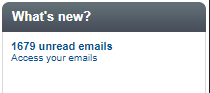

Everyone, from teachers to students to Dawson College – everyone uses email but few have questioned how to use it effectively. Perhaps it is time to think about how we use this convenient technology that is very fast becoming very inconvenient.

Yesterday like any other teacher, I received 15 institutional emails and 3 student MIOs, and this is normal for the second week of the semester. As the semester progresses, the number of communications increases alarmingly. I realized long ago that acting on each of these would not be a good use of my time. In fact, I don’t always read all of them.

All MIOs from students need to be read and addressed in timely fashion.

For institutional emails, I created filters to filter away those messages that I do not need to follow. These are messages such as the Dawson Blues scoreboards and spam from the ‘Dominion Lending Centres’.

After that, I installed the MIO app on my phone, as well as the Microsoft Outlook app, and from there on in, emails became the new text. I read and respond to my emails and my MIOs on the metro, and unless there are messages and MIOs that require extra time and attention, I don’t check my emails or respond outside of that time.

ACCOMMODATING STUDENT SCHEDULES

Students are busy

While I have no data to back it up, I would like to know how much student workloads impact their ability to do the work required of them in class. This question is critical, since any attempt at increasing deep learning and ‘flow’ in the classroom also relies on deep learning and flow outside of the classroom. Critical thinking tasks take time to complete. The student has to be willing to put in the time. Just last week, I called a student in to my office to discuss his essay outline. Together, we reenacted the research process and he point black told me: “but I just don’t have time for that”.

All teachers know that it is very hard for students to find the requisite 3 hours of homework time per week for each class. We make space for students to write in class so as to alleviate their time squeeze outside of the classroom and do all the good participatory teaching. This said, we also know that that increasingly, students aren’t there to do the writing because they have prior engagements. Those of us who make active writing assignments for bonus points are even more acutely aware of this, since after class, there are the inevitable MIOs asking for accommodations to do the writing assignment outside of class. Many of us have also seen the irritation from students who don’t like the idea of doing in-class work for bonus marks.

It’s becoming a conundrum. There is an increasing tension between student availability, which is ever more in question, and the need for student participation in what is essentially participatory learning.

The first step is working together with the students to point out the unsustainable parts of their work mandate, as per their course outlines. Together, we discuss the meaning of course ponderations, and the consequences of having 7 or 8 courses which require 3 hours of in-class time and 3 hours of homework per week. This comes out to a workload ranging from 42 to 48 hours per week. On top of this, most students have part-time jobs, which on standard require 15 – 20 hours of time per week. This means that student workloads range from 57 to 68 hours per week. Added to this, many students travel from far away, and many are experiencing difficult life situations typical of students their age.

Students can’t always come to class

As previously mentioned, the first and most obvious consequence of this is the need to manage obvious occasions when students are unable to attend class. As a general rule, the more participatory the class where group work is emphasized and in-class writing employed, the more student absences affect their work just because a student will have a harder time understanding the instructions, and there will be times when not being in class for group activities will directly penalize their grade.

I begin by asking all students to write me a note about the times they cannot come to class, as per the ISEP requirements, and this in the first two weeks of class. I then endeavor to adapt the class schedule to accommodate the absences. It is a lot of work, but not as much as trying to do the same in the middle of the semester, at the last minute before an important class that will be missed by a student.

The key for this to work is that students truly have to indicate their absences in the first two weeks of the semester. Setting this boundary is crucial.

Firm boundaries help mitigate confusion. Often, students don’t sign up to these field trips until the last minute, and then they ask that I accommodate their absence. When I refuse, if the boundary hasn’t been agreed upon in advance, this often leads to conflict. I have learned to just keep in mind the ultimate list of goals and competencies and ask myself the extent to which the missed material is absolutely necessary to meeting the overall objectives. In the event that the missed material isn’t monumental, I simply use the LEA grading grid to weight other assignments more in compensation for missed work that is hard to make up. This works especially well for tests.

CLASS PLANS.

When we walk into a classroom rushed and distracted, the class doesn’t go well. We struggle to connect not only with the course material, but also with the students.

At first, I didn’t have any class plans. Then I realized that it would be handy to have a document that tells me what I’m supposed to be covering in class, what kind of materials I need to have with me to cover the materials, what kind of deadlines that students need to keep in mind, and what the students need to know to prepare for the next class.

This is especially relevant to in-class writing. You’ll notice at the end of my class plan document, I have a time-line. Time-lines give the instructor an idea of how much time to allocate to each activity in the class. The more activities, including in-class writing activities, the more vital it is to keep track of time being allocated for each. Sometimes when an assignment doesn’t turn out as hoped, it is simply that students didn’t have enough time to complete it. Usually to estimate the time, I take my first estimate and double it for good measure. If I see the class getting bored, I can choose to move on to the next thing and it only means that I have a little more precious time for that next thing.

Class plans change on a continuous basis, and so my first challenge after putting them together was keeping an up to date copy with me. It turns out that trying to print a proper course plan ahead of class was a monumentally bad use of time. In order to circumvent this issue, I downloaded the Dropbox app on my phone. This way, I can access my class plan for the day 10 minutes ahead of the class. I’ve written them in such a way that I can just transfer notes from one section to the blackboard, so the students have a good view of what’s going on, even if they get to class late.

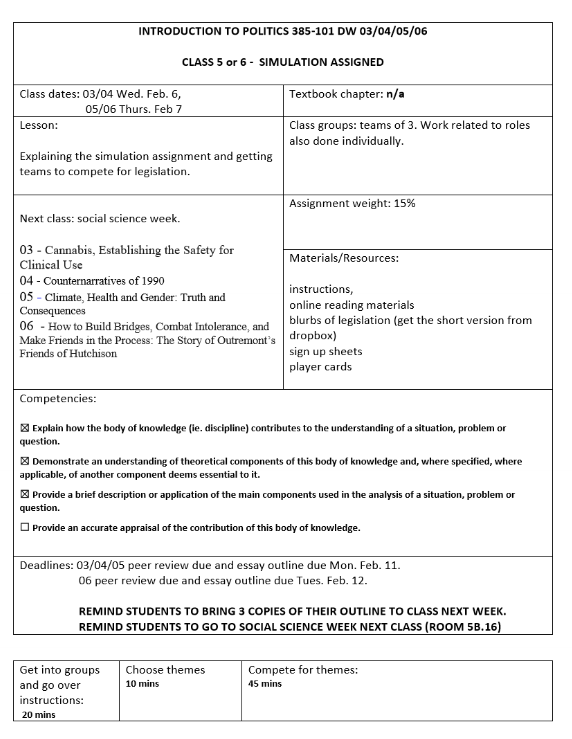

Here’s an example of a class plan for tomorrow morning, which I modified earlier this evening:

BAD USES OF TIME

I discuss optimization here because I believe that there is always a place for it in this discussion, however overall, time pressures won’t be solved by ever better work habits. We need to address the elephant in the room and take a hard look at workloads. I understand that this particular fellowship is not the place to bring this up, but I do so anyway since really, there is no good place to explore this issue.

As mentioned previously, if one takes the time to crunch student workloads, it turns out that they seem pretty unsustainable, especially when factoring in travel and part-time work.

When assessing teaching workloads, the same types of calculations also point to some pretty sobering sustainability issues. My average classes are edging upwards of 40 students each, for a total of 160.

I teach 12 hours per week, I spend anywhere between 3 – 10 hours a week answering student emails and meeting with them. If students hand in an assignment every 2 weeks: 1 essay outline, 2 essay sections, 1 complete essay, 2 tests, plus little assignments… that comes out to on average 80 assignments per week. This represents the reduced student workload that I implemented as a result of reading ‘the Slow Professor’. My students also used to have weekly free writing assignments.

If in the name of productivity I decide to limit my grading to 20 hours a week, this gives me 15 minutes per assignment. I’m not a grading robot, so adding in breaks every hour reduces the time available closer to 12 minutes per assignment. I need to read quick and write even quicker, and time for reflection is not forthcoming.

At this point, my workload is anywhere between 35 – 44 hours, and we haven’t factored in meetings, course prep or anything else. It is safe to say that there are entire weeks where anything resembling ‘flow’ is not an option.

It turns out that students who take pleasure in learning learn better, and teachers who take pleasure in teaching, teach better. This is all difficult to do when both teachers and students are exhausted.

We need to start questioning our workloads. We can reduce the quantity of assigned materials to focus on quality, but that’s only part of the solution. ‘The Slow Professor’ makes clear that in order to fully understand the pressures placed on teachers, and the pressures that teachers place on themselves, we need to understand the impacts of corporatization on the education system. Study upon study indicates a decline in mental health of faculty in institutions across Canada and the United States. Study upon study also indicates that doing less achieves more, especially when it comes to academic scholarship.

We need to define what our end goal is more clearly. This is hard since time spent in contemplation is often time finding questions, not answers. Solutions achieved through this process are less simple, more tentative, situational and organic. The answers are not simple. Often they are just more questions.

Shallow is as shallow does, but as teachers who cultivate time to think might find themselves with strengthened resilience, sense of identity and integrity.

V. COLLEGIALITY

Finally, we get to what’s working. In many campuses across Canada and the United States, academics report that it is becoming harder and harder to find social support in the academy. Daily interaction among colleagues is disappearing. Everyone is too busy. Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber contend that in a climate of ‘accounting’ and efficiency, taking the time to support a colleague belongs to an ‘economy of waste’. When that happens, intellectual life at university dwindles.

I’m happy to relate that almost every day, I intend to go somewhere, meet someone I know in the hall, chat for “way too long” and subsequently rush off, feeling guilty. While the guilt part is not useful, perhaps it is worthwhile to frame such interactions as the conservation of collegiality, which is vital to good teaching.

If I have a Political Science question, I have several places to go, depending on the nature of the question. If I have a question about personal relationship etiquette, I have my go-to colleague, if I have a pedagogical question, I know where to go. If I have a question about workplace conditions, I know who to ask. I have my friends in each profile and certificate for profile and certificate questions, and outside of Dawson College, I’m in regular touch with teachers at Bois de Boulogne, Vanier, Marianopolis etc. etc. I can only hope that my colleagues feel as supported as I do.

Berg and Seeber identify collegiality as the source of support necessary to help manage stress. From my privileged position, though, it is so much more than that. When collegiality works well, educators have access to a veritable ‘hive mind’ of colleagues, all who spend time thinking and who have valuable perspectives and knowledge to contribute to the community. Without my friends, there is no doubt in my mind that my teaching would be so much worse than it is.

I don’t know the secret to ‘creating collegiality’ in places where this has died away. Berg and Seiber’s accounts of efforts to revive collegiality in campuses were awkward at best, insulting and stressful at worst. I made a mental note to be thankful for the wonderful colleagues that surround me and be sure to fill their coffee mugs as much as I can.