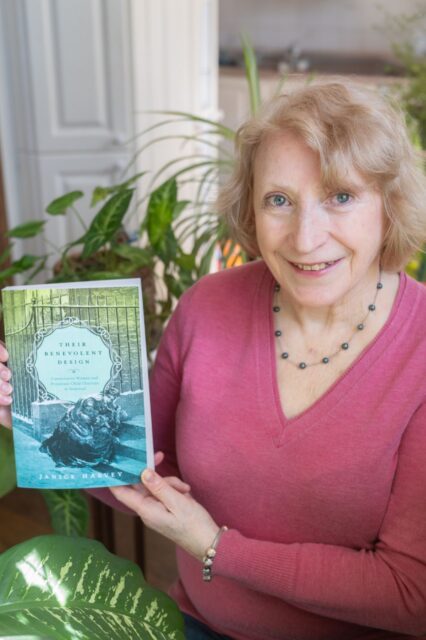

First Prix Paul-André-Linteau awarded to Scholar in Residence Janice Harvey

One of Dawson’s Scholars in Residence, retired history professor and very active researcher Janice Harvey, is the first person to win the Prix Paul-André-Linteau, awarded by the Institut d’histoire de l’Amerique français for the best book on Montreal history published last year.

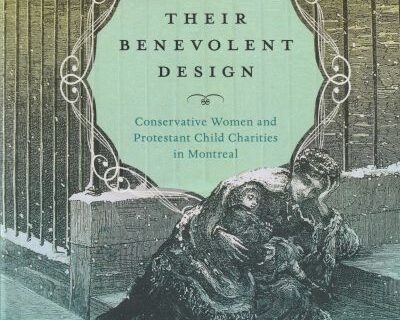

Janice did a Q & A with the Communications Office about her book, Their Benevolent Design. Conservative Women and Protestant Child Charities in Montreal.

What significance does winning the Prix Paul-André-Linteau hold for you and your work? Are you the first recipient of this award?

Janice Harvey: It is a great honour for me to win the Prix Paul-André-Linteau given by the Institut d’histoire de l’Amerique français for the best book published in 2024 on Montreal history. Since this is the first year the prize was awarded, I am the first recipient which makes being chosen even more special. I had written the book to ensure that elite Protestant women’s contribution to Montreal’s history would be recognized; to have the book itself recognized should help to ensure that.

What impact do you hope this book will have on current understandings of social history and charitable work in Quebec?

JH: Until the mid-twentieth century, social services in Quebec, including poor relief, were private and sectarian. Montreal’s Catholic social-services network has received a great deal of scholarly attention, but Their Benevolent Design. Conservative Women and Protestant Child Charities in Montreal is the first book-length study that examines the Anglo-Protestant response to social inequality. As an in-depth study of two institutional child charities, I was able to focus on the bourgeois women who ran them and the children who passed a portion of their childhood within their walls. I hope that this proves to be a valuable contribution to the social history of Quebec.

How did these women-led charities shape social aid and child poverty relief in Montreal during that period?

JH: Their impact was enormous. The city’s Protestant male elite were influenced by liberalism which questioned the advisability of poor relief and led to a moralist, constrained approach to social services. By contrast, the women who founded the child charities had a more conservative, traditional mind-set. Recognizing charity as both a Christian and a class duty, they approached their work from a perspective of need, not morality or forced self-reliance, and thus provided crucial services for vulnerable families when no other support was available. Their benevolent design was anchored by their evangelical faith in religious salvation and structured by their determination to teach poor children “adequate” values. Nonetheless, despite this regulation context, their maternal and caring perspective led them to focus on maintaining adequate conditions inside the institutional homes and developing policies based on protecting the children.

What challenges did the women running these charities face, considering the social conventions of their time?

JH: One of the influential discourses at the time used gendered beliefs about different male and female qualities to propose restricting women’s sphere to the home and limiting their incursions into the world of politics and business. However, this ideology of ‘separate spheres’ was permeable, and charity work, for example, was an accepted, even expected, activity for ‘ladies’ of the elite, existing in what historians have called the social sphere.

Nonetheless, prevailing rules of etiquette and social convention curtailed some of the women’s actions. For example, they accepted norms of propriety by not speaking at their public annual meetings. Furthermore, out of respect for the belief that men and women had different natures, by the last half of the nineteenth century they allocated activities recognized as ‘male’ such as investments and building construction to men’s committees formed specifically to assume these tasks. Some practical limitations also impacted on their work. As women, they did not have the same freedom as men to travel to rescue children from abusive situations, for example, and were reluctant to publicly prosecute apprenticeship masters in cases of abuse.

However, since the care of children and managing a home were recognized as within the female sphere of competence, this discourse gave the women confidence in their own abilities in relation to institutional policies. This proved to be important by the end of the century when several of their policies came under direct attack by members of the male elite who advocated for methods they considered more modern including adoption and scientific philanthropy which called for more restrictions on relief.

Can you share any memorable experiences or anecdotes from your research process?

JH: Three things stand out for me here.

Meeting two former residents in the child charities was a memorable experience. One of them was an elderly man I met in the McGill library when I was working on my MA. He had been taught book binding in the Protestant Orphan Asylum near the turn of the 20th century and now did the binding repairs on the library’s old Cutter books. This experience encouraged me to undertake the study.

As my research unfolded, my appreciation grew for the women, their independence, and their determination. What felt almost like a personal connection with them surprised me and helped me to be more sensitive in the way I treated my analysis of their undertaking.

Finally, while talking about my research with my mother, she told me a story about her experience as a nursing student c.1949 at the Catherine Booth Maternity Hospital, a Salvation Army facility for mothers and children. The CBMH used a monthly open-house policy putting the children on display for potential adopting families. All these years later, she still remembered one little three-year-old girl who regularly asked her whether maybe this time someone would choose her. I often drew on the image of that little girl when I was trying to imagine the children’s experience of institutionalization inside the Montreal charities.

How does this book connect with your ongoing research or scholarly activities since retiring from teaching?

JH: Finalizing the book and getting it through the ‘production’ process was my main project immediately after retirement. Subsequently, I have been continuing work on services for vulnerable youth in the city, this time young boys. My research on the Montreal Boys’ Home from 1870-1905 and its unusual approach to citizenship training was published in 2020. Currently I am researching the Boys’ Home transition to became Weredale House and the impact that joining the Montreal Council of Social Agencies had on their work until their closing in the early 1970s.