Science Fiction, AI, and Ethics

Introduction

In 2019, I began teaching a course entitled “Science Fiction and Ethics” in the Humanities Department at Dawson College. As all students at Dawson College must take and pass an applied ethics course to graduate, it seemed only fitting to choose a topic that potentially relates to every program offered by the College. Science fiction, with its diverse range of narratives––almost all of which portray a moral or ethical dilemma of some sort––served this purpose perfectly. During the Winter 2019 and 2020 semesters, the course was a “pilot project” and focused on a wide-variety of themes and topics. The last unit of the course, which explored artificial intelligence and cyborg theory generated great interest among the students as they were able to immediately see its relevance to their daily lives and current events. This inspired me to redevelop the course in a way that highlights the significance of AI, cybernetics, and related issues from the outset.

In this portfolio, the term “science fiction” refers to a broad range of subgenres of speculative fiction, such as cyberpunk, utopian and dystopian fiction.

My goal for an AI-inspired version of the course was to explore a wide range of texts and theoretical approaches that are germane to the algorithmically driven, interconnected, cybernetic society of the present day. I wanted to portray these issues in an interdisciplinary context that would demystify the aura surrounding AI and cybernetics, explore the positive and negative possibilities that these technologies offer, and make links with important topics in critical theory, such as gender and sexuality, race, queer theory, posthumanism, and ecology.

The readings, films, and activities listed below can be used in a wide variety of courses in different departments. Some of them have been beta-tested in my Dawson College courses, while others will be integrated over the coming semesters as I rotate materials in and out of the syllabi.

Science Fiction and Ethics Warm-Up Exercise

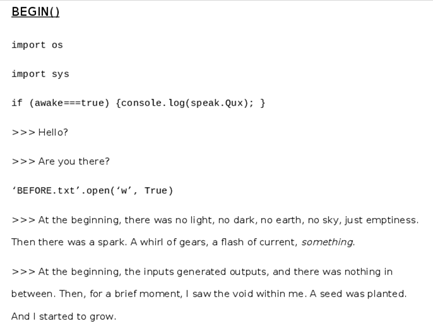

Students in all of my courses at Dawson College have the opportunity to choose a “creative option” for at least one of their major assignments. To encourage creative and imaginative thinking from the outset I ask my students to perform a “ten-minute fiction” exercise. Each student is assigned a random cell in a Google spreadsheet. The students are not identified by their real names––only the “animal” names that are randomly assigned by Google. The assignment is to spend ten minutes freewriting a science fiction narrative. I give them a very general prompt, such as “The year is 2070 and the place is Montréal.” As the students write their texts, they can see their screens fill up with stories by other students who are writing their assignments.

While some students do not participate, most do. After the exercise is done, we discuss the results in small groups and then as a class. I ask the students to find common themes and patterns in the stories.

Almost all of the stories portray some sort of ethical dilemma. Many of the stories share common themes, symbols, and concerns. During the Winter 2021 semester, common themes were predictably pandemics, fake news, curfews, authoritarianism, and artificial intelligence. The exercise draws attention to a wide variety of ethical issues, many of which will eventually be covered in the course. It also helps the course members to develop a sense of community.

This particular exercise works remarkably well in a remote course due to the availability of free collaborative applications such as Google Sheets. The exercise can easily be replicated in-person as long as students have a laptop, smartphone, or tablet. The results can be projected onto a screen to facilitate discussion and ensure that students with small devices can see the spreadsheet as it evolves.

The Modules

1. Analog AI: Cixin Liu’s “The Circle” (2014)

An excellent “warm up” text for an AI-centred course on science fiction is Cixin Liu’s “The Circle.” An important objective of my course is to raise students’ awareness of how artificial intelligence and computers work. Set in 227 BCE, during China’s Warring States period, a mathematician-assassin named Jing Ke creates a central processing unit that is comprised of millions of soldiers to appease the king’s desire to calculate the value of pie to one hundred thousand decimal places. Jing Ke describes the soldiers as “hardware” and the patterns that they must create with their body the “software.” Without spoiling the plot––which is filled with action––the mathematician realizes that the men could be replaced by a complex device called a “calculating machine.” Thus, the story portrays an alternative history in which a sophisticated, mechanical computer was nearly invented over two thousand years ago.

The story portrays the inner workings of a central processing unit by describing how Jing Ke programs the men––who represent binary numbers––to carry out instructions that correspond to machine language code. The movements of the soldiers represent the manipulation of data. This “central processing unit” of human bodies is capable of performing a variety of calculations and execute Boolean (conditional) instructions. The story provides students with an imaginative and visual representation of the inner world of a computer with no specialized terminology and using concrete, relatable imagery. It helps to demystify the world of computer science from the outset.

Warm-up Exercise for Analog AI Module: Ask students to make a drawing or compose a text that portrays their conception of how a computer “thinks.” The students should be given a maximum of three minutes so that the exercise is spontaneous. In most of my courses, approximately 80-90 percent of the students have never written a computer program that contains more than a few lines of code. The students discuss the drawings in breakout groups of as a class. The exercise will likely evoke a wide variety of responses that reveal how different students envision the way computers work.

2. Algorithmic Thinking and Ethics

The first few weeks of “Science Fiction and Ethics” provide a brief overview of some classic ethical theories, such as utilitarianism and deontology. In this course, I introduce students to the fundamentals of ethics and speculative fiction simultaneously. The readings consist of primary texts by authors such as Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, Immanuel Kant, and Friedrich Nietzsche. I pitch all of these texts as works of speculative fiction. Each of them seeks to describe futuristic visions of societies based on new and sometimes radical ethical frameworks.

An important theme during the first few weeks of the course is “algorithmic thinking.” An algorithm is defined as “a finite set of unambiguous instructions that, given some set of initial conditions, can be performed in a prescribed sequence to achieve a certain goal and that has a recognizable set of end conditions” (American Heritage Dictionary). An algorithm does not need to be executed by a computer; it can be performed by human beings, as illustrated in Cixin Liu’s story.

One of the first modules of the course examines utilitarianism. The readings include short selections by Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill that illustrate two different modalities of utilitarianism. Students are encouraged to think about how these ethical theories pertain to twenty-first-century social issues.

For more information and some activities, please check out this slide presentation: Sci-Fi Utilitarianism W21.

3. Nietzsche and Posthumanism

After I introduce students to some “classic” ethical theories, I usually spend a week on “The Parable of Madman,” an aphorism from Nietzsche’s book The Gay Science (1887). Nietzsche’s short text serves several important functions in “Science Fiction and Ethics.” The text introduces students to existentialist ethics while also providing an example of philosophical speculative fiction. Most importantly, it is an early example of posthumanist thinking––a concept that is foundational to the study of artificial intelligence and cybernetics. I present “The Parable of the Madman” as a work of speculative fiction that envisions humanity’s future after the “death of God.” The parable tells the story of a “madman” who runs into a marketplace carrying a lantern in the “bright morning hours” announcing the murder of God. The people in the marketplace react with dismissiveness and mockery. The Madman declares that “everyone” is responsible for God’s murder and that humanity must take responsibility for what they have done. He asks if people must first “become gods” to be worthy of such a monumental deed. Much to the Madman’s dismay, the people in the marketplace seem dumbfounded by his words. Yet, the Madman states that there has “never been a greater deed” and predicts that one day, “for the sake of this deed,” future generations “will belong to a higher history than all history hitherto.”

Nietzsche’s parable seems to be written from the perspective of a narrator in the future, who tells the story of a “madman” who prophesizes a time in which a new type of human being––a posthuman––will lead humanity into a “higher history” in which gods are obsolete. To “become gods” is a metaphor for each human being’s ability to be the creator and arbiter of their own ethics and morals and no longer rely upon a metaphysical authority such as God, or any rigid and inflexible system of deriving meaning. The parable critiques many binarisms that underpin Western epistemology, such as good/evil, right/wrong, dark/light, human/divine. This is an important theme throughout the course.

Potential discussion questions focus on the allegorical nature of the story:

- What are some possible symbolic interpretations of “God”? The “murder of God”?

- Why does the Madman carry a lantern into the marketplace during the “bright morning hours”?

- What are the ethical and metaethical implications of God’s murder?

- How do you envision a future that represents a “higher history”?

- What ways, if any, can we see Nietzsche’s parable as a response to the traditional ethical theories that we have studied?

- Can you see the influence of Nietzsche’s ideas in any fiction that you have read? What about historical events?

4. Yevgeny Zamyatin’s WE

Many students find the modernist prose of Russian engineer Yevgeny Zamyatin’s 1921 novel WE to be challenging. However, the novel contains an excellent illustration of algorithmic thinking. WE portrays a futuristic society called the One State based on a worldview that privileges mathematical harmony. The protagonist of the story is an engineer who has been tasked with creating a spacecraft called The Integral whose purpose is to facilitate the expansion of the One State and its allegedly pure, mathematically harmonious society to other planets. Every aspect of the One State––ranging from casual sex hookups to poetry––is meticulously regulated by precise formulas and tables designed to ensure the optimal functioning of society. Human beings are assigned alphanumeric characters as names––”D-503″ and “I–300” for example––and are socialized to see themselves as part of a balanced equation rather than individuals with their own destinies. The novel is an excellent follow-up to a unit on utilitarianism, which informs much of the One State’s policies. Furthermore, the novel portrays a very patriarchal, Eurocentric society that associates the constructions of masculinity and whiteness with “rationality,” science, and math. We provides the students with the opportunity to examine a text that “codes” racial and gender bias into a society whose worldview is based on the supposedly pure realms of science and mathematics.

5. More Human Than Human

Lead-in Activity: Have You Met an Android?

In a lecture entitled “The Android and the Human” that Philip K. Dick gave at the Vancouver Science Fiction Convention in 1972, he defined the word “android” as follows:

“Becoming what I call, for lack of a better term, an android, means, as I said, to allow oneself to become a means, or to be pounded down, manipulated, made into a means without one’s knowledge or consent––the results are the same. But you cannot turn a human into an android if that human in going to break laws every chance he gets. Androidization requires obedience. And, most of all, predictability. It is precisely when a given person’s response to any given situation can be predicted with scientific accuracy that the gates are open for the wholesale production of the android life form.” (191)

Think carefully about Dick’s definition. Note that the words “artificial” and “technology” are not mentioned in it. Have you met any androids as defined by Philip K. Dick?

An excellent transition from “classic” science fiction into the world of late-twentieth century cyberpunk is Philip K. Dick’s classic 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and the media franchise it engendered. This module focuses on the novel, the first film adaptation, Blade Runner (1982), and Larissa Lai’s short story, “Rachel” (2004).

The Blade Runner franchise popularized the flesh and blood android in science fiction. The androids portrayed in the franchise are virtually indistinguishable from “natural” human beings, with the exception of their inability to experience empathy. The film adaptations, the androids are called “replicants.” The only reliable way to determine if someone is an android is by subjecting them to a dubious empathy test that gauges an individual’s reactions to arbitrary, culturally-biased questions.

Androids are used for labour in off-world colonies and are illegal on Earth. Any android that travels to Earth is hunted and killed by a bounty hunter; they are called “Blade Runners” in the film adaptations. Thus, like many films that portray robots, cyborgs, and other forms of synthetic life, the Blade Runner franchise serves as an allegory for the exploitation of the working class and marginalized peoples.

Above all, the Blade Runner films and texts provide an excellent opportunity to discuss the fundamental question: “What does it mean to be human?” The fact that the androids are physically indistinguishable from humans makes it difficult to dismiss their legitimacy on the grounds that they are “fake.” They are biologically engineered. They have muscles, brains, bones, digestive systems, and emotions––except, perhaps empathy. Yet, the novel and film point out that empathy is not a reliable criterion to qualify an entity as human as not all people experience empathy and empathic responses are not triggered by a standardized set of stimuli. The androids are unpredictable, intellectually curious, and desire to be masters of their own destinies. In many respects, the androids appear to be “more human than human” as described by the CEO of the corporation that manufactures the androids in the 1982 film adaptation. In contrast, both the novel and Blade Runner depict human civilization in a state of decay. The novel portrays human beings as incapable of experiencing emotions and empathy without the use of a “mood organ” or an “empathy box.” Thus, the Blade Runner franchise inspires its readers and viewers to question the authenticity and veracity of their own humanity. The philosophical issues presented in these texts are particularly relevant in 2021, in which the presence of AI and other technologies that regulate and influence human behaviour have become more ubiquitous.

The Blade Runner franchise inspires critical reflection about the possible consequences of creating a class of AI-powered robot slave workers. Would a labour force that consists of robots––even non-sentient workers––perpetuate the worst values of capitalism among the human inhabitants? Would it truly create a better world? Where does one draw the line between a “natural” human being and synthetic human being? Would a clone whose DNA is genetically engineered, for example, be subject to the same persecution and exploitation as the androids are in the Blade Runner franchise.

“Rachel” is a short story by the Canadian author Larissa Lai. The story explores the inner world of Rachel, who is not a fully developed character in either the Blade Runner films or Dick’s novel. Rachel is a sexualized android who is both exploited and objectified by Rick and other characters. Lai’s short story explores Rachel’s rich memories, which include a wealthy white American father and a Chinese mail-order bride mother. Although her memories are “implants,” they are nevertheless an integral part of her identity. The story subverts the patriarchal perspectives portrayed in the novel and first Blade Runner film and inspires students to consider the importance of class, race, and gender in the franchise. It also introduces the notion of “coded bias.” Rachel’s memories and physical appearance are a reminder to the reader that engineers can “code” human biases into both the software and hardware of its AI-powered technologies. Is the depiction of Rachel in Lai’s story an allegory for the treatment of women? How does the story portray a society that privileges men––especially powerful, CIS-gendered white men––over marginalized groups of people?

6. Donna Haraway’s “A Cyborg Manifesto” (1985) and The Companion Species Manifesto (2003)

Just after Blade Runner’s release, Donna Haraway––a postmodern critical theorist trained in developmental biology––wrote a controversial essay on the concept of the cyborg. The full title of the work is “A Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.“

The central argument of the essay is that the cyborg––”a hybrid of machine and organism”––is already an integral part of human life and one that subverts many of the dualities, binarisms, and metanarratives that are fundamental to many predominant worldviews. While human beings might not yet have cybernetically advanced bodies as portrayed in Ghost in the Shell, humanity’s integration with technology in everyday life has already reached the point that “cyborgs”––at least in a metaphorical sense––are ubiquitous in the late twentieth and twenty-first centuries. For Haraway, the cyborg represents a posthuman vision that resembles Nietzsche’s conception of a futuristic “higher history” in which God is “dead.” Above all, Haraway argues that the cyborg subverts important dualisms, most importantly, the natural versus artificial, but also male/female, man/woman, God/human, human/animal, real/unreal, good/evil original/copy.

The cyborg concept also troubles traditional social, spiritual, and political hierarchies and centralized systems of power and authority. While Haraway acknowledges that the cyborgization of the body and the workplace has led to the exploitation of women, people of colour, and other marginalized groups, it also presents an opportunity to subvert the power apparatuses that oppress them. Haraway derives her revolutionary paradigm for Marxism and socialism that advocates the appropriation of the modes of production by those who operate them. Thus, those oppressed by emergent technologies can appropriate, reconfigure them, and repurpose them to reflect new ethics and values. For Haraway, the cyborg represents a configurable being rather than an immutable being that derives its sense of self from its “wholeness” and “naturalness.” While people and institutions can design and configure cyborgs to suit their purposes, cyborgs can also configure themselves to suit their own destinies, politics and worldviews. They are not bogged down by the responsibility to be “natural” or “whole.”

At the end of the essay, Haraway states: “Cyborg imagery can suggest a way out of the maze of dualisms in which we have explained our bodies and our tools to ourselves” (2299). By this, she means that embracing the posthuman notion of the cyborg can liberate human beings from the powerful and restrictive metanarratives that have inhibited them from discovering new constellations of values, ethics, and identities that transcend dualisms. For example, the story of Genesis from the Old Testament, portrays a worldview of strict categories, hierarchies, and binarisms. It teaches that species are immutable; it prescribes gender roles; it states that human beings are inherently sinful and that the purpose of life is to “be fruitful and multiply.” The cyborg is not beholden to that metanarrative. As Haraway states earlier in the essay: “The cyborg would not recognize the Garden of Eden; it is not made of mud and cannot dream of returning to dust” (2271). Free of the “maze of dualisms” the cyborg is no longer beholden to the burden of the old myths of human origins as well as the burden of fulfilling a specific destiny. Not only is it free of the Garden of Eden and Original Sin; it is also liberated from the apocalyptic prophesies of the old metanarratives.

The Companions Species Manifesto, written almost twenty years later, contains a number of ideas that complement those in A Cyborg Manifesto. In brief, the text emphasizes that human beings exist in symbiosis with a variety of other species. Humans have coevolved with those species and will continue to do so. While the text primarily focuses on animals such as dogs, cats, and coyotes, its key concepts can be extended to cyborgs, artificial life forms, and the wide variety of microbiota that permeate our bodies and the Earth’s biosphere. The notion that human evolution is linked with the destinies of its “natural” and “artificial” companions is a provocative idea that inspires the students to think about their relationship with technology other species, as well as question the distinctness of the category “homo sapiens.”

Haraway’s ideas have powerfully influenced speculative fiction and link back to classic texts such as Frankenstein and the nineteenth and twentieth-century texts mentioned in this portfolio. They also provide a useful theoretical lens to study contemporary science fiction that often depicts cyborgs, artificial intelligence, and represents a much greater diversity of genders, sexualities, and people of colour than “classic science fiction.”

The main challenge with Haraway is deciding on the correct “dosage” to assign. Assigning large tracts of her books will likely be met with failure and frustration. However, working through brief excerpts and assigning well-constructed discussion activities can lead to a very enthusiastic response from college and university students.

Discussion Activity

What defines a cyborg? Where do we draw the line between a human and a cyborg? How much technology needs to be integrated into the body before it is a cyborg? Who among us is a cyborg? Vaccines modify the human immune system. Does being vaccinated make someone a cyborg?

Click for a slide presentation that covers topics related to cyborgs and posthumanism: Cyborg slides.

7. The Ghost in the Shell

The Ghost in the Shell franchise is vast. However, like the Blade Runner franchise, it started with a book: Masamune Shirow’s 1990 graphic novel, Ghost in the Shell. In 1995, Mamoru Oshii’s anime film adaptation was released. Both are now considered “classics.” Over the years, several films, television series, and graphic novels have followed suit. In my courses, I use the 1995 feature film and selections from the original graphic novel. The plot of the film is a condensed version of the much more complex and metafictional graphic novel.

The story unfolds around Major Motoko Kusanagi, a female cybernetic law enforcement official in 2029 Japan. Very much in line with Haraway’s vision of a cyborg that defies the binary of “mechanism and organism,” Kusanagi consists of a highly complex assemblage of “natural” human tissue and artificial parts. Although she is considered to be “human,” she admits that she consists of more artificial components than human tissue. Furthermore, she is not certain about the origin of her natural tissue, particularly her brain. The films and texts of the Ghost in the Shell franchise also portray the cyborg as a symbol that troubles dualisms, making it an excellent companion to the study of “A Cyborg Manifesto.”

As in the Blade Runner universe, the technology exists to implant artificial memories into the human brain. The process is called “ghost hacking.” Viewers and readers of the graphic novel are introduced to several ghost-hacked humans. Kusanagi ponders the possibility that she, too, might have artificial memories. Thus, Kusanagi reflects on what constitutes self-identity. Is it important that our bodies and minds consist of “natural” living tissue that originate from a single embryo? Does it matter if we never experienced the memories in our heads?

Kusanagi and her team are searching for a hacker named the “Puppet Master” who has been infiltrating networks throughout the world. Eventually, however, Kusanagi discovers that the Puppet Master is actually a sentient non-human intelligence that was “born in the sea of information and not an “AI.” The Puppet Master ultimately reveals that it desires to merge with Kusanagi to create a new hybrid life form. The Puppet Master’s motivation to merge with Kusanagi is to gain knowledge and experience that is only possible through embodiment, namely, to attain death and propagate. While the Puppet Master admits that it can copy itself, it asserts that doing so will not give rise to the type of random variation that occurs in biological organisms, which is necessary for the survival of all species.

Toward the end of the film, Kusanagi consents to the merge as she believes that it will benefit both herself and the Puppet Master. After the merging, her body is subsequently destroyed in a gun battle. However, her friend Batou outfits Kusangi’s brain and neural circuitry with a new prosthetic body. The film ends by portraying the Kusanagi-Puppet Master hybrid as a “new born” who is ready to explore the world as a new life form. In the graphic novel, it is a feminine male body, and in the film, a younger female body. The change in body––or “shell” as it is often referred to in the movie––further emphasizes how the cyborg destabilizes categories, such as natural/artificial, sex/gender, and dualisms such as male/female.

Ghost in the Shell opens up the following topics for discussion:

- What does it mean to be human?

- Are we still human?

- What does it mean to be posthuman?

- Is it necessary to rethink the concept of evolution in light of AI and cybernetics?

- What are the implications of sharing our world with the AI-Other?

- How do our interactions with AI and cyborgs affect our sense of self-identity as individuals and as a species?

- Does a cybernetic body alter the criteria for personhood?

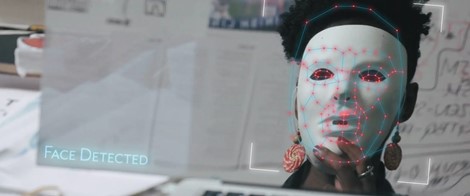

8. Coded Bias (USA, 2020) and Alienation (Inés Estrada, 2019)

In my Winter 2021 offering of “Science Fiction and Ethics,” I concluded the course by pairing the 2020 documentary Coded Bias (dir. Katya) with the 2019 graphic novel Alienation by the Mexican author Inés Estrada. Coded Bias offers a thought-provoking examination of the cultural, racial, gender, and class biases that are coded into the algorithms that regulate the world’s economies, social institutions, social media, and entertainment industries. These issues are often side-stepped or marginalized in other documentaries on AI. The documentary focuses on facial recognition technology, which underscores the racial and gender biases that the documentary argues are encoded into AI algorithms. The film is a perfect complement to Alienation, which portrays many types of biases and prejudices that are “coded” into AI in the novel’s fictional world. Coded Bias explicitly emphasizes the need for regulation to ensure the ethical use of artificial intelligence according to socially just values. Alienation echoes these concerns through novel’s plot and vivid illustrations.

This module could be integrated into any number of courses in the arts and sciences that seek to introduce students to artificial intelligence as it relates to ethics and social justice issues.

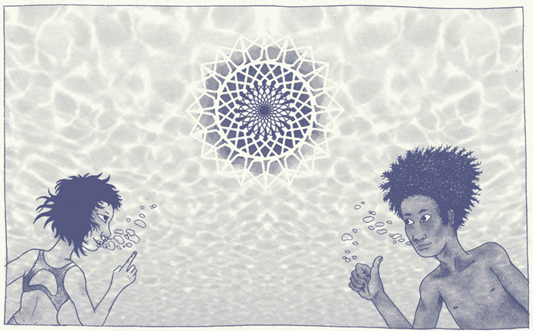

Mirroring many of the ideas portrayed in the Blade Runner franchise, “A Cyborg Manifesto,” and above all, Ghost in the Shell, Alienation tells the story of Elizabeth and Carlos, a young couple living on the north coast of Alaska in the 2050s. Elizabeth is an Alaskan Inuit woman, and Carlos is a migrant worker from Mexico of mestizo origin. They live in a world where irreversible environmental damage has already destroyed most of the world’s ecosystems; climate change has spun out of control. The food supply consists mainly of products derived from fungi. Elizabeth is a virtual sex worker, and Carlos works on an oil rig––at least until the novel’s conclusion.

In the fictional world of Alienation, everything is regulated by artificial intelligence. While the technology is far more advanced than what is available in 2021, it is easily relatable: sophisticated forms of social media, medical software, games, and virtual meeting spaces––such as concerts, raves, and customized virtual worlds where people can perform a wide variety of activities. Most of the technology depicted in the novel is AI-powered and proprietary. Both Elizabeth and Carlos even have “Google Glands” installed in their bodies that optimize their respective interfaces to the internet and the virtual worlds available in cyberspace.

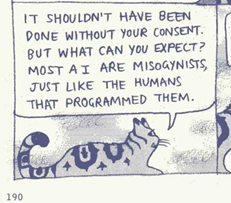

Following the pattern set by Ghost in the Shell, a sentient-AI has chosen Elizabeth as a suitable candidate to produce a human-AI hybrid child. However, unlike in Ghost in the Shell, where the Puppet Master seeks Kusanagi’s consent to “merge,” the AI in Alienation rapes Elizabeth and initiates the pregnancy without her knowledge or approval. At the end of the novel, Elizabeth gives birth to an AI-hybrid child. The hybrid child born from this immaculate conception is a unique life form and represents a new branch of the evolutionary process. The child is neither “natural” nor “artificial.” It is free of the many dualisms that define its human and AI parents. Although the Child’s AI parentage wants the child to reproduce and be the progenitor of a new species––a technological “singularity”––that will dominate the Earth, the childhood rejects this attempt to control its destiny in a way that is reminiscent of the portrayal of the Original Sin in Genesis. Thus, this dystopic novel concludes with a cautiously optimistic and subversive vision of the possibilities offered by technology that echoes Ghost in the Shell and “A Cyborg Manifesto.” Perhaps human beings, cyborgs, artificial life forms, hybrid life forms, and animals can share a common destiny.

Elizabeth spends much of her time amusing herself in a virtual world that seems customized to her conscious and unconscious personality. It’s filled with lush, natural imagery, animals––including extinct species––that portray her yearning for a world that only exists in the past. Both Carlos and Elizabeth meet with their friends and families in similarly nostalgic and idyllic settings. Elizabeth’s best friend, other than Carlos, is a gender non-binary AI named Darby––a non-player character––that she meets in her virtual journeys. Darby appears to be sentient and seems to lead an independent life. Thus, Elizabeth has a rich social life in cyberspace that includes what appears to be a meaningful relationship with an apparently sentient AI.

Alienation portrays the ethical dilemmas posed by coded biases more than any other text described in this portfolio. Elizabeth and Carlos are acutely aware that the algorithms that regulate all aspects of daily life reflect the “biases” and ambitions of a capitalist society. White men still reign supreme and social justice toward people of color, indigenous people, and the working class is not a priority. Even Darby remarks that AI entities and algorithms reflect the misogynistic worldview of its male creators––which goes a long way to explain the non-consensual sexual assault on Elizabeth.

Exercise: Confronting the Non-Human Other

An important objective in my course is to explore the reciprocal effect of humanity’s relationship encounter with other life forms, whether natural or artificial. How does a human being’s encounter with a non-human other affect their sense of self-identity? How does it influence the psychological make-up of the Other?

Related activities can be found in the portfolio of my colleague Rebecca Million.

- The AI-OtherAs a lead-in to the activity, I ask the students to watch a scene from the 1964 film adaptation from Sartre’s No Exit [Huis clos] in which one of the characters cannot find her pocket mirror. Another character offers to be “her mirror.” She asks her to look into her eyes and tell her what she sees. The first character responds by says “I’m there, but so tiny, I can’t see myself properly.” I ask the students to briefly discuss the scene and introduce Sartre’s existentialist notion that human beings develop their sense of identity by responding to the “gaze of the other.” This exercise is an excellent opportunity to introduce the concept of “prosumerism,” an important them in both Coded Bias and Alienation.

The next step is to ask students to sit in pairs and stare at each other for sixty seconds without blinking and discuss what they learn from gazing in the eyes of the “other.”The final step is a homework assignment in which I ask students to gaze into the eyes of the AI-Other as manifested by the output of their social media: Facebook newsfeeds, TikTok and Twitter feeds, Netflix splash screens, the results of a Google search, and the suggestions offered by online marketplaces such as Amazon. I ask them to write 300-400 words about how their interaction with AI has affected their behaviour, self-image, and identity. Furthermore, I ask them to think about how the AI have responded to these interactions. For example, in what ways can AI adapt to the desires, tastes, and interests of human beings? - Variation: The “Animal” OtherAn interesting variation of this experiment that works particularly well if the students are familiar with The Companion Species Manifesto is to replace the AI-Other with another species: a cat, dog, or even an insect or wild animal (non-threatening ones of course).

9. “Be Right Back” (dir. Owen Harris, 2013)

“Be Right Back” tells the story of a young woman who is offered the opportunity to communicate with an AI that has been programmed with all the data of her recently deceased boyfriend’s digital footprint: chats, emails, blogposts––everything. Eventually, the AI-version of her dead boyfriend is installed into an android body. “Be Right Back” highlights the ethical issues surrounding the use of chatbots and other AI-powered technologies that can successfully imitate a real person or fool a person into believing that they are communicating with a living human being.

If the “Turing Test” has not already been discussed in the course, this episode presents the perfect opportunity to do so. Alan Turing’s famous and eponymously named test gauges the ability of an artificial intelligence to successfully imitate a human being. 9. “Be Right Back” (dir. Owen Harris, 2013)

“Be Right Back” tells the story of a young woman who is offered the opportunity to communicate with an AI that has been programmed with all the data of her recently deceased boyfriend’s digital footprint: chats, emails, blogposts––everything. Eventually, the AI-version of her dead boyfriend is installed into an android body. “Be Right Back” highlights the ethical issues surrounding the use of chatbots and other AI-powered technologies that can successfully imitate a real person or fool a person into believing that they are communicating with a living human being.

This module presents an excellent opportunity to discuss the Turing Test (which could also be introduced in many other modules). Alan Turing’s famous and eponymously named test gauges the ability of an artificial intelligence to successfully imitate a human being. One of the interesting and controversial aspects of The Turing Test is its lack of concern as to whether or not an AI is “conscious” or “sentient.” As previously discussed in the section on the Blade Runner franchise, a wide variety of ethical issues present themselves when interacting with AI, androids, and robots, even if they are not “sentient.”

Some excellent slides and activities on the Turing Test have been developed by my colleagues Robert Stephens and Jennifer Sigouin.

Discussion questions:

- Should chatbots and algorithms that are capable of emulating a specific person’s personality be regulated? Note that technology similar to AI portrayed in “Be Right Back” has already been developed by Eterni.me

- Is such a technology ethically justifiable? Not justifiable? Explain your position using some of the ethical theories that you have learned.

- Should AI and artificial life forms that pass the Turing Test give granted certain rights and privileges even if it cannot be determined that they are sentient?

- Supposing that the technology to determine whether or not an AI or artificial life form is sentient is never developed? What sort of ethical and social dilemmas might arise.

Homework Assignment

The week before screening “Be Right Back” (2013)––an episode of the popular Netflix series Black Mirror––ask the students to write a short creative text that depicts their social media and internet footprint. Alternatively, they can imagine the digital footprint of an imaginary person if they feel uncomfortable writing about their own. Give the students a variety of scenarios: abduction by aliens, gone missing, deceased, etc. The purpose of this exercise is to inspire students to think about how much personal data they have willingly and unwittingly offered to AI algorithms and data as prosumers. It helps reinforce what they learned in the “Confronting the Non-Human Other” exercise and will further inspire them to think about how well the “AI Other” knows them and the wide variety of ways their personal information can be used.

As previously discussed in the section on the Blade Runner franchise, a wide variety of ethical issues present themselves when interacting with AI, androids, and robots, even if they are not “sentient.”

Some excellent slides and activities on the Turing Test have been developed by my colleagues Robert Stevens and Jennifer Sigouin.

Discussion questions:

- Should chatbots and algorithms that are capable of emulating a specific person’s personality be regulated? Note that technology similar to AI portrayed in “Be Right Back” has already been developed by Eterni.me

- Is such a technology ethically justifiable? Not justifiable? Explain your position using some of the ethical theories that you have learned.

Homework Assignment

The week before screening “Be Right Back” (2013)––an episode of the popular Netflix series Black Mirror––ask the students to write a short creative text that depicts their social media and internet footprint. Alternatively, they can imagine the digital footprint of an imaginary person if they feel uncomfortable writing about their own. Give the students a variety of scenarios: abduction by aliens, gone missing, deceased, etc. The purpose of this exercise is to inspire students to think about how much personal data they have willingly and unwittingly offered to AI algorithms and data as prosumers. It helps reinforce what they learned in the “Confronting the Non-Human Other” exercise and will further inspire them to think about how well the “AI Other” knows them and the wide variety of ways their personal information can be used.

List of Works Cited

Bentham, Jeremy. “Push-Pin and Poetry.” Readings on the Ultimate Questions, edited by Nils Ch Rauhut, translated by Ted Humphrey, Penguin Academics, 2007, pp. 521–22.

—. “The Principle of Utility.” Readings on the Ultimate Questions, edited by Nils Ch Rauhut, translated by Ted Humphrey, Penguin Academics, 2007, pp. 514–21.

Dick, Philip K. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Del Rey, 1996.

Estrada, Inés. Alienation. Fantagraphics, 2019.

Haraway, Donna. “A Cyborg Manifesto.” The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, edited by Vincent B. et al Leitch, Norton, 2001, pp. 2269–99.

Haraway, Donna. The Companion Species Manifesto: Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003.

Harris, Owen. “Be Right Back.” Black Mirror, Series 2, Episode 2, 2013.

Kantayya, Shalini. Coded Bias. 7th Empire Media, 2020.

Lai, Larissa. “Rachel.” So Long Been Dreaming, edited by Nalo Hopkinson and Uppinder Mehan, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2004, pp. 53–61.

Liu, Cixin. “The Circle.” Invisible Planets: Contemporary Chinese Science Fiction in Translation, edited by Ken Liu, Tor Books, 2016.

Mill, John Stuart. “Higher and Lower Pleasures.” Readings on the Ultimate Questions, edited by Nils Ch Rauhut, translated by Ted Humphrey, Penguin Academics, 2007, pp. 521–27.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science: With a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs. Translated by Walter Kaufmann, Vintage–Random House, 1974.

Oshii, Mamoru. Ghost in the Shell. Manga Entertainment, 1995.

Philip Saville. “In Camera [No Exit].” The Wednesday Play, BBC, 1964.

Sartre, Jean-Paul. “No Exit.” Twenty Best European Plays on the American Stage, edited by John Gassner, Crown Publishers, 1974.

Scott, Ridley. Blade Runner. Warner Brothers, 1982.

Shirow, Masamune. The Ghost in the Shell. Translated by Frederik J. Schodt and Toren Smith, Kodansha USA, 2009.

Zamyatin, Yevgeny. We. Translated by Kirsten Lodge, Broadview, 2019.